Google Chrome and Apple Safari browsers both overhauled their extension systems in a way that annoyed ad blockers. The motives of the two giants were arguably different, as were the political consequences.

Credit: Patrick Emerson // Flickr

For Google, the start of 2019 was inaugurated with a concert of casseroles. The company had made changes to the extension system in its Chrome browser. These software decisions have kept many ad blockers from working properly. Many saw it as a way for Google to defend its advertising revenue, and in the face of the outcry, the giant had to revise certain details.

Very similar software reforms took place at Apple from the summer of 2018, on the Safari browser. With the release of Safari 13 last week, the old add-on system was definitely shelved. Several ad blockers have had to downgrade their functionality on the Apple browser over the past year. The media noise this time was much more subdued.

Google and Apple both had legitimate reasons to overhaul their browser extension systems. The main objective of these measures was probably not to hinder ad blockers, who are above all collateral victims. Whether or not the two giants are concerned about their setbacks, or even find an interest in accentuating these tribulations, is a whole different story.

When Google declares war on malware ...

Google Chrome represents 65% of the web browser market. If we also count the open source version Chromium - on which players such as Opera, Vivaldi, Kiwi or Brave are based - the Mountain View giant holds a small empire. Who says large population of users, says need to be effective in maintaining order.

Extensions to a web browser are like small applications that are added to the main software. As with all applications, they exist in large numbers and at varying levels of quality. Most importantly, some hide malware behind an innocuous appearance. Platforms are making efforts to remove malicious extensions, for example using machine learning to detect suspicious behavior, but it's a never-ending struggle.

Just two weeks ago, Google swept away malicious extensions that spoofed the names of respected adblockers, AdBlock Plus and uBlock Origin. The fraudulent modules had been downloaded by more than 2 million people. Since antiviruses already regard Chrome as healthy software, harmful additions to it tend to fall through the cracks.

All this means that Google has an interest in cementing its browser. It also makes Chrome or Chromium more stable and faster, as it is less susceptible to friction and bugs. The giant accelerated its efforts from October 2018, and in January 2019 published its Manifesto V3, which details a set of measures to be applied over an undetermined horizon. At the end of May, for example, the firm announced to restrict the access of extensions to user data.

"It's as if Google assumes that all Chrome extensions are malicious, but hey, they're the ones who run their store," cryptographer Matthew Green of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore told WIRED. “I have the impression that Google treats its extensions as if they were radioactive waste. Maybe that's what they really are. Currently, installs of malicious extensions on Chrome are estimated to have dropped 89% compared to early 2018.

… And when Apple wants seamless software…

In Apple's walled garden, it is quite easy to uproot weeds. Especially in Safari, which only captures 3,5% of the browser market, and is therefore not a prime target for delinquency. But the guardian of the orchard also wants that there is not a leaf which protrudes, and that all the software of its ecosystem are as integrated as possible between them for a “seamless” experience. A term widely used by the apple and which, in good Spanish, denotes a smooth experience.

It all goes back to two software mechanisms that Apple introduced with iOS 9 in 2013. By themselves, they're perfectly harmless. App Extensions allows an app to extend its functionality over another app. Combined with an API called Content Blocker, the mechanism allows an application to tell Safari to block a particular element of a web page according to a series of rules.

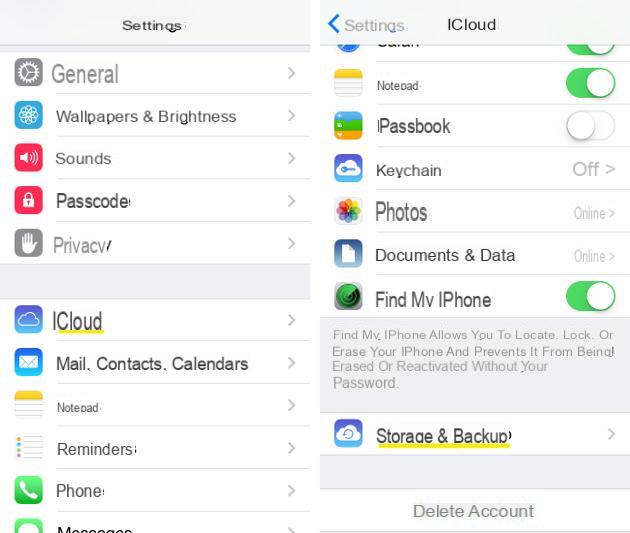

After a few years, Apple realized that developers didn't really need to write specific extensions for Safari anymore, since a standard app in the App Store could do the same job. The company announced in summer 2018 that it would be phasing out the old extension system in the near future. Developers were advised to port their code to an "app extension" and put it on the App Store. Today, on the Safari 13 delivered with iOS 13, the old extensions are no longer recognized.

... ad blockers drool over it

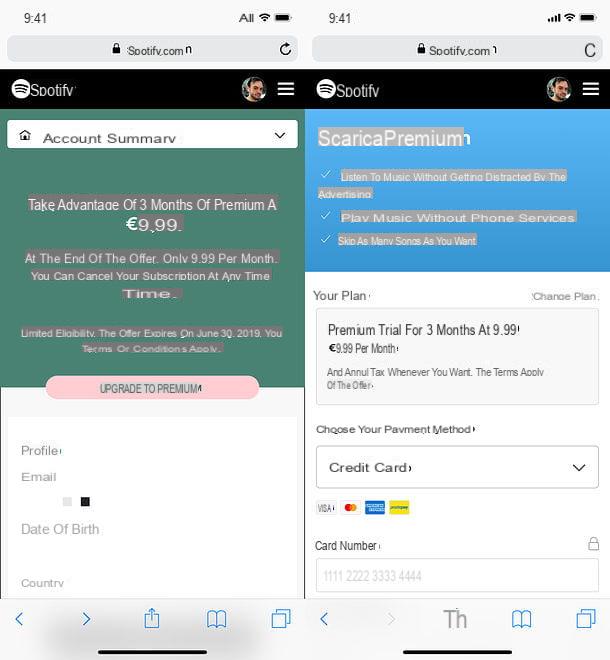

Whether at Google or at Apple, content blocking APIs are based on a system of filtering rules. An extension can say "if such and such an element of the site looks like this or that, it is surely an advertising display and it will have to be blocked". But in order to block ads in real life, you have to set a lot of rules. Very much.

On Chrome, adblockers previously relied on a software interface called the Web Request API. In V3 of its Chrome manifesto, Google expressed the wish to replace it with a Declarative Net Request API. That had a number of rules originally limited to 30, a number considered to be very low. Apple Safari allows him 000 rules, which is hardly better.

Blocking delay is only a few milliseconds

The reasons for this constraint are not explained, but we can assume - among other honest motivations - that it would be related to software performance. Google's V3 argues that certain extensions can have "a negative impact on the user experience", which would justify "the restriction of the blocking capabilities [of HTTP requests] of the webRequest API". A later study, published by the parent company of the extension Ghostery, on the contrary indicates that the delay related to the blocking is only a few milliseconds.

Following the outcry, Google announced to raise the limit of rules of its API to 90, then 000, and finally 120. Adblockers developers still consider this insufficient. Competing browsers Opera, Brave and Vivaldi, all three focusing on digital rights and freedoms and all three based on Chromium, have said they will not endorse Google's changes.

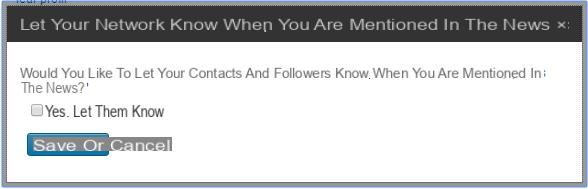

Apple's API also has limitations on other aspects, such as the ability to whitelist certain content. If you want to financially support your favorite smartphone news site (hello, that's us!), You may want to whitelist it to lift the ad block when you're on it. The same, for example, for the channels of YouTubers that you like. With Safari Content Blocking, this is still possible, but by telling Safari to disable the ad blocker on specific sites. The user is therefore forced to go through Apple settings.

Warning to devs making VPN apps for iOS that block content… Apple is starting to reject apps that do this. Both @Malwarebytes and @AdGuard have been affected now. If you need this, better talk to Developer Relations ASAP about your options!https://t.co/wSmrc5Jj8q

— Thomas Reed (@thomasareed) July 22, 2018

Several extensions then preferred to withdraw from Safari, if only for the time to rewrite their code - by ridding it of additional functions, such as those of VPN. AdGuard temporarily packed up in July 2018 (it has since returned, and today displays a promotional banner "Safari 13 has disabled your ad blocker? Here's a 30% discount for you!").

Malwarebytes boss Thomas Reed tweeted shortly after that his ad blocker was also affected. “After a while, everything changed. Apple just changed its mind, and there is no easy solution to that, ”observed Tomasz Koperski, CTO of AdBlock, at Fast Company in September 2018. Safari has few enough users that adblockers can afford to momentarily step off the ship. Such maneuvers would not be possible with Chrome, on which these extensions depend for their financial survival.

Political echoes

Google and Apple have implemented similar measures. Since the former has partially backed down, Apple is de facto the more restrictive of the two. We ignore the shares of legitimate and dubious intentions that led to these results, but it is clear that this is not trivial on the political level.

Needless to say, the economic model of Google is very largely based on advertising. Adblockers are therefore directly harmful to the income of the firm. In a purely cynical world where public opinion does not exist, the Mountain View giant would surely not hesitate to put a stick in their wheels. But fortunately, even the biggest heavyweights in Silicon Valley are still susceptible to scandals.

Google's hegemony makes it a company that is highly scrutinized by competition authorities. Even if the giant has largely passed between the drops so far, it is in his best interest not to add a layer. Its power over digital is such that there is a phenomenon well known in international relations: the balance of power, which means that weaker actors (such as ad blockers, but also individual users) will have tendency to gang up on him to thwart any abuse.

The US Congress in Washington, which opened an antitrust investigation against four digital giants.

Apple is primarily a smartphone maker, and its advertising revenue is negligible. Unless you imagine a convoluted diplomatic maneuver, there is no reason to think that the Cupertino company has a particular animosity towards ad blockers. But we must admit, the Apple readily cultivates the idea that it knows better than everyone what is good for users. Hence his probable lack of remorse at the lamentations of adblockers.

However, this indifference is in contradiction with other ideals displayed by the company of Tim Cook. Ad blockers are important protectors of privacy because they keep many cookies and tracking devices at bay. Considering how Cupertino waves the banner of confidentiality, this policy has something to be seen as a "double standard".

Either way, if you value your ad blockers, you can try an alternative to browsers from the two giants - like Firefox, Brave, Opera, and more.

The best internet browsers on Android for your needs

The best internet browsers on Android for your needs

Whether it is to better protect your privacy, or for very specific functions, it may be interesting to install an alternative browser to Google Chrome on Android. It exists on the Google Play Store ...